Tarzan and the Champion by Edgar Rice Burroughs

The lost colony of Maya performed barbaric human sacrifices. Tarzan finds an unexpected ally in the fight against them.

Tarzan and the Champion

"Six—seven—eight—nine—ten!" The referee stepped to a neutral corner and hoisted Mullargan's right hand. "The win-nah and new champion!" he shouted.

For a moment the audience, which only partially filled Madison Square Garden, sat in stunned and stupefied silence; then there was a burst of applause, intermingled with which was an almost equal volume of boos. It wasn't that the booers questioned the correctness of the decision—they just didn't like Mullargan, a notoriously dirty fighter. Doubtless, too, many of them had had their dough on the champion.

Joey Marks, Mullargan's manager, and the other man who had been in his corner crawled through the ropes and slapped Mullargan on the back; photographers, sportswriters, police, and a part of the audience converged on the ring; jittery news-commentators bawled the epochal tidings to a waiting world.

The former champion, revived but a bit wobbly, crossed the ring and proffered a congratulatory hand to Mullargan. The new champion did not take the hand. "G'wan, you bum," he said, and turned his back.

"One-Punch" Mullargan had come a long way in a little more than a year—from amateur to preliminary fighter, to Heavyweight Champion of the World; and he had earned his sobriquet. He had, in truth, but one punch; and he needed but that one—a lethal right to the button. Sometimes he had had to wait several rounds before he found an opening, but eventually he had always found it. The former champion, a ten-to-one favorite at ringside, had gone down in the third round. Since then, One-Punch Mullargan had fought but nine rounds; yet he had successfully defended his championship six times, leaving three men with broken jaws and one with a fractured skull. After all, who wishes his skull fractured?

So One-Punch Mullargan decided to take a vacation and do something he always had wanted to do but which fate had always heretofore intervened to prevent. Several years before, he had seen a poster which read, "Join the navy and see the world;" he had always remembered that poster; and now, with a vacation on his hands, Mullargan decided to go and see the world for himself, without any assistance from Navy or Marines.

"I ain't never seen Niag'ra Falls," said his manager. "That would be a nice place to go for a vacation. If we was to go there, that would give Niag'ra Falls a lot of publicity too."

"Niag'ra Falls, my foot!" said Mullargan. "We're goin' to Africa."

"Africa," mused Mr. Marks. "That's a hell of a long ways off—down in South America somewheres. Wot you wanna go there for?"

"Huntin'. You see them heads in that guy's house what we were at after the fight the other night, didn't you? Lions, buffaloes, elephants. Gee! That must be some sport."

"We ain't lost no lions, kid," said Marks. There was a note of pleading in his voice. "Listen, kid: stick around here for a couple more fights; then you'll have enough potatoes to retire on, and you can go to Africa or any place you want to—but not me."

"I'm goin' to Africa, and you're goin' with me. If you want to get some publicity out of it, you better call up them newspaper bums."

Sports-writers and camera-men milled about the champion on the deck of the ship ten days later. Bulbs flashed; shutters clicked; reporters shot questions; passengers crowded closer with craning necks; a girl elbowed her way through the throng with an autograph album.

"When did he learn to write?" demanded a Daily News man.

"Wise guy," growled Mullargan.

"Give my love to Tarzan when you get to Africa," said another.

"And don't get fresh with him, or he'll take you apart," interjected the Daily News man.

"I seen that bum in pitchers," said Mullargan. "He couldn't take nobody apart."

"I'll lay you ten to one he could K.O. you in the first round," taunted the Daily News man.

"You ain't got ten, you bum," retorted the champion.

A heavily laden truck lumbered along the edge of a vast plain under the guns of the forest which had halted here, sending out a scattering of pickets to reconnoiter the terrain held by the enemy. Why the tree army never advanced, why the plain always held its own—these are mysteries.

And the lorry was a mystery to the man far out on the plain, who watched its slow advance. He knew that there were no tracks there, that perhaps since creation this was the first wheeled vehicle that had ever passed this way.

A white man in a disreputable sun-helmet drove the truck; beside him sat a black man; sprawled on top of the load were several other blacks. The lengthening shadow of the forest stretched far beyond the crawling anachronism, marking the approach of the brief equatorial twilight.

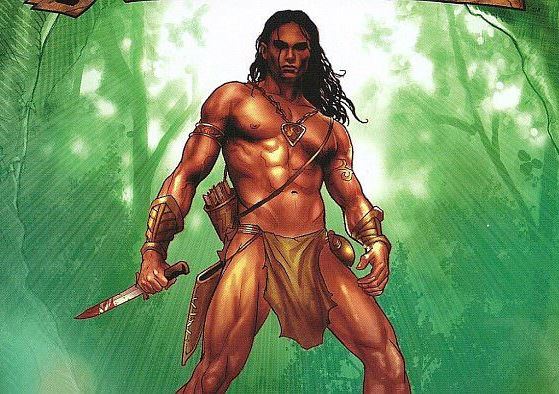

The man out upon the plain set his course so that he might meet the truck. He moved with an easy, sinuous stride that was almost catlike in its smoothness. He wore no clothes other than a loin-cloth; his weapons were primitive: a quiver of arrows and a bow at his back, a hunting-knife in a rude scabbard at his hip, a short, stout spear that he carried in his hand. Looped across one shoulder and beneath the opposite arm was a coil of grass rope. The man was very dark, but he was not a Negro. A lifetime beneath the African sun accounted for his bronzed skin.

Upon his shoulder squatted a little monkey, one arm around the bronzed neck. "Tarmangani, Nkima," said the man, looking in the direction of the truck.

"Tarmangani," chattered the monkey. "Nkima and Tarzan will kill the tarmangani." He stood up and blew out his cheeks and looked very ferocious. At a great distance from an enemy, or when upon the shoulder of his master, little Nkima was a lion at heart. His courage was in inverse ratio to the distance that separated him from Tarzan, and in direct ratio to that which lay between himself and danger. If little Nkima had been a man, he would probably have been a gangster and certainly a bully; but he still would have been a coward. Being just a little monkey, he was only amusing. He did, however, possess one characteristic which, upon occasion, elevated him almost to heights of sublimity. That was his self-sacrificing loyalty to his master, Tarzan.

At last the man on the truck saw the man on foot, saw that they were going to meet a little farther on. He shifted his pistol to a more accessible position and loosened it in its holster. He glanced at the rifle that the boy beside him was holding between his knees, and saw that it was within easy reach. He had never been in this locality before, and did not know the temper of the natives. It was well to take precautions. As the distance between them lessened, he sought to identify the stranger.

"Mtu mweusi?" he inquired of the boy beside him, who was also watching the approaching stranger.

"Mzungu, bwana," replied the boy.

"I guess you're right," agreed the man. "I guess he's a white man, all right, but he's sure dressed up like a native."

"Menyi wazimo," laughed the boy.

"I got two crazy men on my hands now," said the man. "I don't want another." He brought the truck to a stop as Tarzan approached.

Little Nkima was chattering and scolding fiercely, baring his teeth in what he undoubtedly thought was a terrifying snarl. Nobody paid any attention to him, but he held his ground until Tarzan was within fifty feet of the truck; then he leaped to the ground and sought the safety of a tree near by. After all, what was the use of tempting fate?

Tarzan stopped beside the truck and looked up into the white man's face. "What are you doing here?" he asked.

Melton, looking down upon an almost naked man, felt his own superiority; and resented the impertinence of the query. Incidentally, he had noted that the stranger carried no firearms.

"I'm drivin' a lorry, buddy," he said.

"Answer my question." This time Tarzan's tone had an edge to it.

Melton had had a hard day. As a matter of fact, he had had a number of hard days. He was worried, and his nerves were on edge. His hand moved to the butt of his pistol as he formulated a caustic rejoinder, but he never voiced it. Tarzan's arm shot out; his hand seized Melton's wrist and dragged the man from the cab of the truck. An instant later he was disarmed.

Nkima danced up and down upon the branch of his tree and hurled jungle billingsgate at the enemy, intermittently screaming at Tarzan to kill the tarmangani. No one paid any attention to him. That was a cross that Nkima always had to bear. He was so little and insignificant that no one ever paid any attention to him.

The blacks on the truck sat in wide-eyed confusion. The thing had happened so suddenly that it had caught their wits off guard. They saw the stranger dragging Melton away from the truck, shaking him as a dog shakes a rat. Tarzan had learned from experience that there is no surer way of reducing a man to subservience than by shaking him. Perhaps he knew nothing of the psychology of the truth, but he knew the truth.

The latter was a powerful man, but he was helpless in the grip of the stranger; and he was frightened, too. There was something more terrifying about this creature than his superhuman strength. There was the quite definite sensation of being in the clutches of a wild beast, so that his reactions were much the same as they had been many years before when he had been mauled by a lion—something of a fatalistic resignation to the inevitable.

Tarzan stopped shaking Melton and turned his eyes on the boy with the rifle, who had jumped down from the truck. "Throw down the rifle," he said in Swahili.

The boy hesitated. "Throw it down," ordered Melton; and then, to Tarzan: "What do you want of me?"

"I asked you what you were doing here. I want an answer."

"I'm guidin' a couple of bloomin' Yanks."

"Where are they?"

Melton shrugged. "Gawd only knows. They started out early this morning in a light car, and told me to keep along the edge of the forest. Said they'd come back an' meet me later in the day. They're probably lost. They're both balmy."

"What are they doing here?" asked Tarzan.

"Hunting."

"Why did you bring them here? This is closed territory."

"I didn't bring 'em here; they brought me. You can't tell Mullargan nothing. He's one of those birds that knows it all. He don't need a guide; what he needs is a keeper. He's Heavyweight Champion of the World, and it's gone to his head. Try to tell him anything, and he's just as likely as not to slap you down. He's knocked the boys around something awful. I never saw such a rotten bounder in my life. The other one ain't so bad. He's Mullargan's manager. That's a laugh. Manager, my eye! All he says is, 'Yes, kid!' 'Okay, kid!' and all he wants to do is get back to New York. He's scared to death all the time. I wish to hell they was both back in New York. I wish I was rid of 'em."

"Are they out alone?" asked Tarzan.

"Yes."

"Then you may be rid of them. This is lion country. I have never seen them so bad."

Melton whistled. "Then I got to push on and try to find 'em. I don't like 'em, but I'm responsible for 'em. You"—he hesitated—"you ain't goin' to try to stop me, are you?"

"No," said Tarzan. "Go and find them, and tell them to get out of this country and stay out." Then he started on toward the forest.

When he had gone a short distance, Melton called to him. "Who are you, anyway?" he demanded.

The ape-man paused and turned around. "I am Tarzan," he said.

Again Melton whistled. He climbed back into the cab of the truck and started the motor; and as the heavy vehicle got slowly under way, Tarzan disappeared into the forest.

The sun swung low into the west, and the lengthening shadow of the forest stretched far out into the plain. A light car bounced and jumped over the uneven ground. There were two men in the car. One of them drove, and the other braced himself and held on. His eyes were red-rimmed; he sneezed almost continuously.

"Fer cripe's sake, kid, can't you slow down?" wailed Marks. "ain't this hay-fever bad enough without you tryin' to jounce the liver out of me?"

For answer Mullargan pressed the accelerator down a little farther.

"You won't have no springs or no tires or no manager, if you don't slow down."

"I don't need no manager no more." That struck Mullargan as being so funny that he repeated it. "I don't need no manager no more; so I bounces him out in Africa. Gee, wouldn't dat give the guys a laugh!"

"Don't get no foolish ideas in your head, kid. You need a smart fella like me, all right. All you got is below them big cauliflower ears of yours."

"Is zat so?"

"Yes, zat's so."

Mullargan slowed down a little, for it had suddenly grown dark. He switched on the lights. "It sure gets dark in a hurry here," he commented. "I wonder why."

"It's the altitude, you dope," explained Marks.

They rode on in silence for a while. Marks glanced nervously to right and left, for with the coming of night, the entire aspect of the scene had changed as though they had been suddenly tossed into a strange world. The plain was dimly lined in the ghostly light of pale stars; the forest was solid, impenetrable blackness.

"Forty-second Street would look pretty swell right now," observed Marks.

"So would some grub," said Mullargan; "my belly's wrapped around my backbone. I wonder what became of that so-an'-so. I told him to keep right on till he met us. Them English is too damn' cocky—think they know it all, tellin' me not to do this an' not to do that. I guess the Champeen of the World can take care of himself, all right."

"You said it, kid."

The silence of the plain was broken by the grunting of a hunting lion. It was still some distance away, but the sound came plainly to the ears of the two men.

"What was that?" queried Mullargan.

"A pig," said Marks.

"If it was daylight, we might get a shot at it," observed Mullargan. "A bunch of pork chops wouldn't go so bad right now. You know, Joey, I been thinkin' me and you could get along all right without that English so-an'-so."

"Who'd drive the truck?"

"That's so," admitted Mullargan; "but he's got to stop treatin' us like we was a couple o' kids and he was our nurse-girl. Pretty soon I'm goin' to get sore and hand him one."

"Look!" exclaimed Marks. "There's a light—it must be the truck."

When the two cars met, the tired men dropped to the ground and stretched stiffened limbs and cramped muscles.

"Where you been?" demanded Mullargan.

"Coming right along ever since we broke camp," replied Melton. "You know this bus can't cover the ground like that light car of yours, and you must have covered a lot of it today. Any luck?"

"No. I don't believe there's any game around here."

"There's plenty. If you'll make a permanent camp somewhere, as I've been telling you, we'll get something."

"We seen some buffaloes today," said Marks, "but they got away."

"They went into some woods," explained Mullargan. "I followed 'em in on foot, but they got away."

"Lucky for you they did," observed Melton.

"What you mean—lucky for me?"

"If you'd shot one of 'em, you'd probably have been killed. I'd rather face a lion any day than a wounded buffalo."

"Maybe you would," said Mullargan, "but I ain't afraid of no cow."

Melton shrugged, turned and set the boys to making camp. "We've got to camp where we are," he said to the other two whites. "We couldn't find water now; and we've got enough anyway, such as it is. Anyway, tomorrow we must turn back."

"Turn back?" exclaimed Mullargan. "Who says we gotta turn back? I come here to hunt, an' I'm goin' to hunt."

"I met a man back there a way who says this is closed territory. He told me we'd have to get out."

"Oh, he did, did he? Who the hell does he think he is, tellin' me to get out? Did you tell him who I was?"

"Yes, but he didn't seem to be much impressed."

"Well, I'll impress him if I see him. Who was he?"

"His name is Tarzan."

"Dat bum? Does he think he can run me out of Africa?"

"If he tells you to leave this part of Africa, you'd better," Melton advised.

"I'll leave when I get good an' damn' ready," said Mullargan.

"I'm ready to go right now," said Marks, between sneezes. "This here Africa ain't no place for a guy with hay-fever."

The boys were unloading the truck, hurrying to make camp. One was building a fire preparatory to cooking supper. There was much laughter, and now and then a snatch of native song. One of the boys, carrying a heavy load from the truck, accidentally bumped into Mullargan and threw him off balance. The fighter swung a vicious blow at the black with his open palm, striking him across the side of his head and knocking him to the ground.

"You'll look where you're goin' next time," he growled.

Melton came up to him. "That'll be all of that," he said. "I've stood it as long as I'm goin' to. Don't ever hit another of these boys."

"So you're lookin' for it too, are you?" shouted Mullargan. "All right, you're goin' to get it."

Before he could strike, Melton drew his pistol and covered him. "Come on," he invited. "I'm just waitin' for the chance to plead guilty to killin' you in self-defense."

Mullargan stood staring at the gun for several seconds; then he turned away. Later he confided to Marks: "Them English ain't got no sense of humor. He might of seen I was just kiddin'."

The evening meal was a subdued affair. Conversation could not accurately have been said to lag, since it did not even exist until the meal was nearly over; then the grunting of a lion was heard close to the camp.

"There's that pig again," said Mullargan. "Maybe we can get him now."

"What pig?" asked Melton.

"You must be deaf," said Mullargan. "Can't you hear him?"

"Cripes!" exclaimed Marks. "Look at his eyes shine out there."

Melton rose and stepping to the side of the truck switched on the spotlight and swung it around upon the eyes. In the circle of bright light stood a full-grown lion. Just for a moment he stood there; then he turned and slunk off into the darkness.

"Pig!" said Mullargan, disgustedly.

A chocolate-colored people are the Babangos, with good features and well-shaped heads. Their teeth are not filed; yet they are inveterate man-eaters. There are no religious implications in their cannibalism, no superstitions. They eat human flesh because they like it, because they prefer it to any other food; and like true gourmets, they know how to prepare it. They hunt man as other men hunt game animals, and they are hated and feared throughout the territory that they raid.

Recently, word had been brought to Tarzan that the Babangos had invaded a remote portion of that vast domain which, from boyhood, he had considered his own; and Tarzan had come, making many marches, to investigate. Behind him, moving more slowly, came a band of his own white-plumed Waziri warriors, led by Muviro, their famous chief...

It was the morning following Tarzan's encounter with Melton. The ape-man was swinging along just inside the forest at the edge of the plain, his every sense alert. There was no slightest suggestion of caution in his free stride and confident demeanor; yet he moved as silently as a shadow. He saw the puff adder in the grass and the python waiting in the tree to seize its prey from above, and he avoided them. He made a little detour, lest he pass beneath a trumpet tree from which black ants might drop upon and sting him.

Presently he halted and turned, looking back along the edge of the forest and the plain. Neither you nor I could have heard what he heard, because our lives have not depended to a great extent upon the keenness of our hearing. There are wild beasts which have notoriously poor eyesight, but none with poor hearing or a deficient sense of smell. Tarzan, being a man and therefore poorly equipped by nature to survive in his savage world, had developed all his senses to an extraordinary degree; and so it was that now he heard pounding hoofs in the far distance long before you or I could have. And he heard another sound—a sound as strange to that locale as would be the after-kill roar of a lion on Park Avenue: the exhaust of a motor.

They were coming closer now; and they were coming fast. And now there came another sound, drowning out the first—the staccato of a machine-gun. Presently they tore past him—a herd of zebra; and clinging to their flank was a light car. One man drove, and the other pumped lead from a submachine gun into the fleeing herd. Zebra fell, some killed, some only maimed; but the car sped on, its occupants ignoring the suffering beasts in its wake.

Tarzan, helpless to prevent it, viewed the slaughter in cold anger. He had witnessed the brutality of game-hogs before, but never anything like this. His estimate of man, never any too high, reached nadir. He went out into the plain and mercifully put out of their misery those of the animals which were hopelessly wounded, following the trail of destruction in the direction that the car had taken. Eventually he would come upon the two men again, and there would be an accounting.

Far ahead of him, the survivors of the terrified herd plunged into a rock gully, and clambering up the opposite side, disappeared over the ridge as Mullargan brought the car to a stop near the bottom.

"Gee!" he exclaimed. "Was dat sport! When I gets all my heads up on a wall, I'll make that Park Avenue guy look like a piker."

"You sure cleaned 'em up, kid," said Marks. "That was some shootin'."

"I wasn't a expert rifleman in the Marine Corps for nothin', Joey. Now if I could just run into a flock of lions—boy!"

The forest came down into the head of the gorge, and the trees grew thickly to within a hundred yards of the car. There was a movement among the trees there, but neither of the dull-witted men were conscious of it. They had lighted cigars and were enjoying a few moments of relaxation.

"I guess we better start back an' mop up," said Mullargan. "I don't want to lose none of 'em. Say, at this rate I ought to take back about a thousand heads if we put in a full month. I'll sure give them newspaper bums somep'n to write about when I get home. I'll have one of them photographer bums take my pitcher settin' on top of a thousand heads—all kinds. That'll get in every newspaper in the U.S."

"It sure will, kid," agreed Marks. "We'll sure give Africa a lot of publicity." As he spoke, his eyes were on the forest up the gorge. Suddenly his brows knitted. "Say, kid, lookit! What's that?"

Mullargan looked, and then cautiously picked up the machine-gun. "S-s-sh!" he cautioned. "That's a elephant. What luck!" He raised the muzzle of the weapon and squeezed the trigger. An elephant trumpeted and lurched out into the open. It was followed by another and another, until seven of the great beasts were coming toward them; then the gun jammed.

"Hell!" exclaimed Mullargan. "They'll get away before I can clear this."

"They ain't goin' away," said Marks. "They're comin' for us."

The elephants, poor of eyesight, finally located the car. Their trunks and their great ears went up, as, trumpeting, they charged; but by that time Mullargan had cleared the gun and was pouring lead into them again. One elephant went down. Others wavered and turned aside. It was too much for them—too much for all but one, a great bull, which, maddened by the pain of many wounds, carried the charge home.

The sound of the machine-gun ceased. Mullargan threw the weapon down in disgust. "Beat it, Joey!" he yelled; "the drum's empty."

The two men tumbled over the opposite side of the car as the bull struck it. The weight of the great body, the terrific impact, rolled the car over, wheels up. The bull staggered and lurched forward, falling across the chassis, dead.

The two men came slowly back. "Gee!" said Mullargan. "Look wot he went an' done to that jalopy! Henry wouldn't never recognize it now." He got down on his hands and knees and tried to peer underneath the wreck.

Marks was shaking like an aspen. "Suppose he hadn't of croaked," he said; "where would we of been? Wot we goin' to do now?"

"We gotta wait here until the truck comes. Our guns is all underneath that mess. Maybe the truck can drag the big bum off. We gotta have our guns."

"I wish to Gawd I was back on Broadway," said Marks, sneezing, "where there ain't no elephants or no hay."

Little Nkima was greatly annoyed. In the first place, the blast of the machine-gun had upset him. It had frightened him so badly that he had abandoned the sanctuary of his lord and master's shoulder and scampered to the uttermost pinnacle of a near-by tree. When Tarzan had gone out on the plain, he had followed; and he didn't like it at all out on the plain, because the fierce African sun beat down, and there was no protection. And he was further annoyed because he had continued to hear the nerve-shattering sound intermittently for quite some time, and it came from the direction in which they were going. As he scampered along behind, he scolded his master; for little Nkima saw no sense in looking for trouble in a world in which there was already more than enough looking for you.

Tarzan had heard the sound of the gunning, the squeals of hurt elephants and the trumpeting of angry elephants; and he visualized the brutal tragedy as clearly as though he saw it with his eyes; and his anger rose so that he forgot the law of the white man, for Tantor the elephant was his best friend. It was a wild beast, a killer, that set out at a brisk trot in the direction from which the sounds had come.

The sounds that had come to the ears of Tarzan and the ears of Nkima had come also to other ears in the dense forest beyond the gorge. Their owners were slinking through the shaded gloom on silent, stealthy feet to reconnoiter. They came warily, for they knew the sounds meant white men; and many white men with guns were bad medicine. They hoped that there were not too many.

As Tarzan reached the edge of the gorge and looked down upon the scene below, other eyes looked down from the opposite side.

These other eyes saw Tarzan; but the trees and the underbrush hid them from him, and the wind being at his back, their scent was not carried to his nostrils.

Of the two men in the gorge, Marks was the first to see Tarzan. He called Mullargan's attention to him, and the two men watched the ape-man descending slowly toward them. Nkima, sensing trouble, remained at the summit, chattering and scolding. Tarzan approached the two men in silence.

"Wot you want?" demanded Mullargan, reaching for the gun at his hip.

"You kill?" asked Tarzan, pointing at the dead elephant, and in his anger, reverting to the monosyllabic grunts which were reminiscent of his introduction to English many years before.

"Yes—so what?" Mullargan's tone was nasty.

"Tarzan kill," said the ape-man, and stepped closer. He was five feet from Mullargan when the latter whipped his pistol from its holster and fired. But quick as Mullargan had been, Tarzan had been quicker. He struck the weapon up, and the bullet whistled harmlessly into the air; then he tore the gun from the other's hand and hurled it aside.

Mullargan grinned, a twisted, sneering grin. The poor boob was pretty fresh, he thought, getting funny like that with the Heavyweight Champion of the World. "So you're dat Tarzan bum," he said; then he swung that lethal right of his straight for Tarzan's chin.

He was much surprised when he missed. He was more surprised when the ape-man dealt him a terrific blow on the side of the head with his open palm, a blow that felled him, half-stunned.

Marks danced about in consternation and terror. "Get up, you bum," he yelled at Mullargan; "get up and kill him."

Nkima jumped up and down at the edge of the gorge, hurling defiance and insults at the tarmangani. Mullargan came slowly to his feet. Instinctively, he had taken a count of nine. Now there was murder in his heart. He rushed Tarzan, and once again the ape-man made him miss; then Mullargan fell into a clinch, pinning Tarzan's right arm and striking terrific blows above one of the ape-man's kidneys, to hurt and weaken him.

With his free hand Tarzan lifted Mullargan from his feet and threw him heavily to the ground, falling on top of him. Steel-thewed fingers sought Mullargan's throat. He struggled to free himself, but he was helpless. A low growl came from the throat of the man upon him. It was the growl of a beast, and it filled the champion with a terror that was new to him.

"Help, Joey! Help!" he cried. "The so-an'-so's killin' me."

Marks was the personification of futility. He could only hop about, screaming: "Get up, you bum; get up and kill him!"

Nkima hopped about too, and screamed; but he hopped and screamed for a very different reason from that which animated Marks, for he saw something that the three men, their whole attention centered on the fight, did not see. He saw a horde of savages coming down out of the forest on the opposite side of the gorge.

The Babangos, realizing that the three men below them were thoroughly engrossed and entirely unaware of their presence, advanced silently, for they wished to take them alive and unharmed. They came swiftly, a hundred sleek warriors, muscled and hard, a hundred splendid refutations of the theory that the eating of human flesh makes men mangy, hairless and toothless.

Marks saw them first, and screamed a warning; but it was too late, for they were already upon him. By the weight of their numbers, they overwhelmed the three men, burying Tarzan and Mullargan beneath a dozen sleek dark bodies; but the ape-man rose, shaking them from him for a moment. Mullargan saw him raise a warrior above his head and hurl him into the faces of his fellows, and the champion was awed by this display of physical strength so much greater than his own.

This momentary reversal was brief—there was too many Babangos even for Tarzan. Two of them seized him around the ankles, and three more bore him backward to the ground; but before they succeeded in binding him, he had killed one with his bare hands.

Mullargan was taken with less difficulty; Marks with none. The Babangos bound their hands tightly behind their backs; and prodding them from behind with their spears, drove them up the steep gorge side into the forest.

Little Nkima watched for a moment; then he fled back across the plain.

The gloom of the forest was on them, depressing further the spirits of the two Americans. The myriad close-packed trees, whose interlaced crowns of foliage shut out the sky and the sun, awed them. Trees, trees, trees! Trees of all sizes and heights, some raising their loftiest branches nearly two hundred feet above the carpet of close-packed phyrnia, amoma, and dwarf bush that covered the ground. Loops and festoons of lianas ran from tree to tree, or wound like huge serpents around their boles from base to loftiest pinnacle. From the highest branches others hung almost to the ground, their frayed extremities scarcely moving in the dead air; and other, slenderer cords hung down in tassels with open thread work at their ends, the air roots of the epiphytes.

"Wot you suppose they goin' to do with us?" asked Marks. "Hold us for ransom?"

"Mabbe. I don' know. How'd they collect ransom?"

Marks shook his head. "Then what are they goin' to do with us?"

"Why don't you ask that big bum?" suggested Mullargan, jerking his head in the general direction of Tarzan.

"Bum!" Marks spat the word out disgustedly. "He made a bum outta you, big boy. I wisht I had a bum like that back in Noo York. I'd have a real champeen then. He nearly kayoed you with the flat of his hand. What a haymaker he packs!"

"Just a lucky punch," said Mullargan. "Might happen to anyone."

"He picks you up like you was a flyweight; but when he turns you down you land like a heavyweight, all right. I suppose 'at was just luck."

"He ain't human. Did you hear him growl? Just like a lion or somep'n."

"I wisht I knew what they was goin' to do with us," said Marks.

"Well, they ain't agoin' to kill us. If they was, they would of done it back there when they got us. There wouldn't be no sense in luggin' us somewheres else to kill us."

"I guess you're right, at that."

The footpath that the Babangos followed with their captives wound erratically through the forest. It was scarcely more than eighteen inches wide, a narrow trough worn deep by the feet of countless men and beasts through countless years. It led at last to a rude encampment on the banks of a small stream near its confluence with a larger river. It was the site of an abandoned village in a clearing not yet entirely reclaimed by the jungle.

As the three men were led into the encampment, they were surrounded by yelling women and children. The women spat upon them, and the children threw sticks at them until the warriors drove them off; then, with ropes about their necks, they were tied to a small tree.

Marks, exhausted, threw himself upon the ground; Mullargan sat with his back against the tree; Tarzan remained standing, his eyes examining every detail of his surroundings, his mind centered upon a single subject—escape.

"Cripes," said Marks. "I'm all in."

"You ain't never used your dogs enough," said Mullargan, unsympathetically. "You was always keen on me doin' six miles of road work every day while you loafed in an automobile."

"What was that?" suddenly demanded Marks.

"What's what?"

"Don't you hear it—them groans?" The sound was coming from the direction of the stream, which they could not see because of intervening growth.

"Some guy's got a bellyache," said Mullargan.

"It sounds awful," said Marks. "I wisht I was back in Gawd's country. You sure had a hell of a bright idea—comin' to this Africa. I wisht I knew what they was goin' to do with us."

Mullargan glanced up at Tarzan. "He ain't worryin' none," he said, "and he ought to know what they're goin' to do with us. He's a wild man himself."

They had been speaking in whispers, but Tarzan had heard what they said. "You want to know what they're going to do to you?" he asked.

"We sure do," said Marks.

"They're going to eat you."

Marks sat up suddenly. He felt his throat go dry, and he licked his lips. "Eat us?" he croaked. "You're kiddin', Mister; they ain't no cannibals no more, only in movin' pitchers an' story-books."

"No? You hear that moaning coming from the river?"

"Uh-huh."

"That part of it's worse than being eaten."

"They're preparing the meat—making it tender. Those are men or women or little children that you hear—there are several of them. Two or three days ago, perhaps, they broke their arms and legs in three or four places with clubs; then they sank them in the river, tying their heads up to sticks; so they can't drown by accident or commit suicide. They'll leave them there three or four days; then they'll cut them up and cook them."

Mullargan turned a sickly yellowish white. Marks rolled over on his side and was sick. Tarzan looked down on them without pity.

"You are afraid," said Tarzan. "You don't want to suffer. Out on the plain and in the forest are the zebra and elephant that you left to suffer, perhaps for many days."

"But they're only animals," said Mullargan. "We're human bein's."

"You are animals," said the ape-man. "You suffer no more than other animals, when you are hurt. I am glad that the Babangos are going to make you suffer before they eat you. You are worse than the Babangos. You had no reason for hunting the zebra and the elephant. You could not possibly have eaten all that you killed. The Babangos kill only for food, and they kill only as much as they can eat. They are better people than you, who will find pleasure in killing."

For a long time the three were silent, each wrapped in his own thoughts. Above the noises of the encampment rose the moans from the river. Marks commenced to sob. He was breaking. Mullargan was breaking too, but with a different reaction.

He looked up at Tarzan, who still stood, impassive, above them. "I been thinkin', Mister," he said, "about what you was sayin' about us hurtin' the animals an' killin' for pleasure. I ain't never thought about it that way before. I wisht I hadn't done it."

A little monkey fled across the hot plain. He made a detour to avoid the lumbering truck following in the wake of the hunters. Shortly thereafter he took to the trees and swung through them close to the edge of the plain. He was a terrified little monkey, constantly on the alert for the many creatures to which monkey meat is an especial delicacy. It was sad that such an ardent nemophilist should be afraid in the forest, but that was because Histah the snake and Sheeta the panther were also arboreal. There were also large monkeys with very bad dispositions, which it were wise to avoid; so little Nkima traveled as quietly and unobtrusively as possible. It was seldom that he traveled, or did anything else, with such singleness of purpose; but today not even the most luscious caterpillar, the most enticing fruits, or even a nest of eggs could tempt him to loiter. Little Nkima was going places, fast...

Melton saw the carcasses of zebra pointing the way the hunters had gone. He was filled with anger and disgust, and he cursed under his breath. When he came to the edge of the gorge, he saw the wreck of the automobile lying beneath the body of a bull elephant; but he saw no sign of the two men. He got out and went down into the gorge.

Melton was an experienced tracker. He could read a story in a crushed blade of grass or a broken twig. A swift survey of the ground surrounding the wrecked automobile told him a story that filled him with concern—for himself. With his rifle cocked, he climbed back up the side of the gorge toward the truck, turning his eyes often back toward the forest on the opposite side. It was with a sigh of relief that he turned the truck about and started back across the plain.

"The bounders had it coming to them," he thought. "There's nothing I can do about it but report it, and by that time it will be too late."

That night the Babangos feasted, and Tarzan learned from snatches of their conversation that they were planning to commence the preparation of him and the two Americans the following night; but Tarzan was of no mind to have his arms and legs broken. He lay down close to Mullargan.

"Turn on your side," he whispered. "I am going to lie with my back to yours. I'll try to untie the thongs on your wrists; then you can untie mine."

"Oke," said Mullargan.

Out in the forest toward the plain a lion roared, and the instant reaction of the Babangos evidenced their fear of the king of beasts. They replenished their beast-fires and beat their drums to frighten away the marauder. They were not lion men, these hunters of humans; but after a while, hearing no more from the lion, the savages, once again feasting, dancing, drinking, relaxed their surveillance; and Tarzan was able to labor uninterruptedly for hours. It was slow work, for his hands were so bound that he could use the fingers of but one of them at a time; but at least one knot gave to his perseverance. After that it was easier, and in another half-hour Mullargan's hands were free. With two hands, he could work more rapidly; but time was flying. It was long past midnight. There were signs that the orgy would soon be terminated; then, Tarzan knew, guards would be placed over them. At last he was free. Marks' bonds responded more easily.

"Crawl on your bellies after me," Tarzan whispered. "Make no noise." Mullargan's admission of his regret for the slaughter of the zebra had determined Tarzan to give the two men a chance to escape—that, and the fact that Mullargan had helped to release him. He felt neither liking nor responsibility for them. He did not consider them as fellow-beings, but as creatures further removed from him than the wild beasts with which he had consorted since childhood: those were his kin and his fellows.

Tarzan inched across the clearing toward the forest. Had he been alone, he would have depended upon his speed to reach the sanctuary of the trees where no Babangos could have followed him along the high-flung pathways that the apes of Kerchak had taught him to traverse; but the only chance the two behind him had was that of reaching the forest unobserved.

They had covered scarcely more than a hundred feet when Marks sneezed. Asthmatic, he had reacted to some dust or pollen that their movement had raised from the ground. He sneezed, not once but continuously; and his sneezing was answered by shouts from the encampment.

"Get up and run!" directed Tarzan, leaping to his feet; and the three raced for the forest, followed by a horde of yelling savages.

The Babangos overtook Marks first, the result of neglecting his road-work; but they caught Mullargan too, just before he reached the forest. They caught him because he had hesitated momentarily motivated by what was possibly the first heroic urge of his life, to attempt to rescue Marks. When they were upon him, and both rescue and escape were no longer possible, One-punch Mullargan went berserk.

"Come on, you bums!" he yelled, and planted his famous right on a black chin. Others closed in on him and went down in rapid succession to a series of vicious rights and lefts. "I'll learn you," growled Mullargan, "to monkey with the Heavyweight Champeen of the World!" Then a warrior crept up behind him and struck him a heavy blow across his head with the haft of a spear, and One-punch Mullargan went down and out for the first time in his life.

Tarzan, perched upon the limb of a tree at the edge of the clearing, had been an interested spectator, correctly interpreting Mullargan's act of heroism. It was the second admirable trait that he had seen in either of these tarmangani, and it moved him to a more active contemplation of their impending fate. Death meant nothing to him, unless it was the death of a friend, for death is a commonplace of the jungle; and his, the psychology of the wild beast, which, walking always with death, is not greatly impressed by it.

But self-sacrificing heroism is not a common characteristic of wild beasts. It belongs almost exclusively to man, marking the more courageous among them. It was an attribute that Tarzan could understand and admire. It formed a bond between these two most dissimilar men, raising Mullargan in Tarzan's estimation above the position held by the Babangos, whom he looked upon as natural enemies. Formerly, Mullargan had ranked below the Babangos, below Ungo the jackal, below Dango the hyena.

Tarzan still felt no responsibility for these men, whom he had been about to abandon to their fate; but he considered the idea of aiding them, perhaps as much to confound and annoy the Babangos as to succor Mullargan and Marks.

Once again Nkima crossed the plain, this time upon the broad, brown shoulder of Muviro, chief of the white-plumed Waziri. Once again he chattered and scolded, and his heart was as the heart of Numa the lion. From the shoulder of Muviro, as from the shoulder of Tarzan, Nkima could tell the world to go to hell—and did.

From his slow-moving lorry, Melton saw, in the distance, what appeared to be a large party of men approaching. He stopped the lorry and reached for his binoculars.

When he had focused them on the object of his interest, he whistled.

"I hope they're friendly," he thought. One of his boys had told him that the Babangos were raiding somewhere in this territory, and the evidence he had seen around the wrecked automobile seemed to substantiate the rumor. He saw that the boy beside him had his rifle in readiness, and drove on again.

When they were closer, he saw that the party consisted of some hundred white-plumed warriors. They had altered their course so as to intercept him. He thought of speeding up the truck and running through them. The situation looked bad to him, for this was evidently a war party. He called to the boys on top of the load to get out the extra rifles and to commence firing if he gave the word.

"Do not fire at them, Bwana," said one of the boys; "they would kill us all if you did. They are very great warriors."

"Who are they?" asked Melton.

"The Waziris. They will not harm us."

It was Muviro who stepped into the path of the truck and held up his hand.

Melton stopped.

"Where have you come from?" asked the Waziri chief.

Melton told him of the gorge and what he had found in its bottom.

"You saw no other white men than your two friends?" asked Murivo.

"Yesterday, I saw a white man who called himself Tarzan."

"Was he with the others when they were captured?"

"I do not know."

"Follow us," said Muviro, "and camp at the edge of the forest. If your friends are alive, we will bring them back."

Nkima's actions had told Muviro that Tarzan was in trouble, and this new evidence suggested that he might have been killed or captured by the same tribe that had surprised the other men.

Melton watched the Waziri swing away at a rapid trot that would eat up the miles rapidly; then he started his motor and followed...

At the cannibal encampment, the Babangos, sleeping off the effects of their orgy, were not astir until nearly noon. They were in an ugly mood. They had lost one victim, and many of them were nursing sore jaws and broken noses as a result of their encounter with One-punch Mullargan.

The white men were not in much better shape: Mullargan's head ached, while Marks ached all over; and every time he thought of what lay in store for him before they would kill him, he felt faint.

"They breaks our arms and legs in four places," he mumbled, "and, then they soaks us in the drink for three days to make us tender. The dirty bums!"

"Shut up!" snapped Mullargan. "I been tryin' to forget it."

Tarzan, knowing that the Waziri were not far behind him, returned to the edge of the plain to look for them. Alone, and in broad daylight, be knew that not even he could hope to rescue the Americans from the camp of the Babangos. All day he loitered at the edge of the plain; and then, there being no sign of the Waziri, he swung back through the trees toward the cannibal encampment as the brief equatorial twilight ushered in the impenetrable darkness of the forest night.

He approached the camp from a new direction, coming down the little stream in which the remaining victims were stilt submerged. Above the camp, his nostrils caught the scent of Numa the lion and Sabor the lioness; and presently he made out their dim forms below him. They were slinking silently toward the scent of human flesh, and they were ravenously hungry. The ape-man knew this, for the scent of an empty lion is quite different from that of one with a full belly. Every wild beast knows this; so it is far from unusual to see lions that have recently fed pass through a herd of grazing herbivores without eliciting more than casual attention.

The silence and hunger of these two stalking lions boded ill for their intended prey.

A dozen warriors approached Mullargan and Marks. They cut their bonds and jerked the two men roughly to their feet; then they dragged them to the center of the camp, where the chief and the witch-doctor sat beneath a large tree. Warriors stood in a semi-circle facing the chief, and behind them were the women and children.

The two Americans were tripped and thrown to the ground upon their backs: and there they were spread-eagled, two warriors pinioning each arm and leg. From the foliage of the tree above, an almost naked white man looked down upon the scene. He was weighing in his mind the chances of effecting a rescue, but he had no intention of sacrificing himself uselessly for these two. Beyond the beast-fires two pairs of yellowish-green unblinking eyes watched. The tips of two sinuous tails weaved to and fro. A pitiful moan came from the stream near by; and the lioness turned her eyes in that direction, but the great black-maned male continued to glare at the throng within the encampment.

The witch-doctor rose and approached the two victims. In one hand he carried a zebra's tail, to which feathers were attached; in the other a heavy club. Marks saw him and commenced to whimper. He struggled and cried out:

"Save me, kid! Save me! Don't let 'em do this to me!"

Mullargan muttered a half-remembered prayer. The witch-doctor began to dance around them, waving the zebra's tail over them and mumbling his ritualistic mumbo-jumbo. Suddenly he leaped in close to Mullargan and swung his heavy club above the pinioned man; then Mullargan, Heavyweight Champion of the World, tore loose from the grasp of the warriors and leaped to his feet. With all the power of his muscles and the weight of his body, he drove such a blow to the chin of the witch-doctor as he had never delivered in any ring; and the witch-doctor went down and out with a broken jaw. A shout of savage rage went up from the assembled warriors, and a moment later Mullargan was submerged by numbers.

The lioness approached the edge of the stream and stretched a taloned paw toward the head of one of the Babangos' pitiful victims, a woman. The poor creature screamed in terror, and the lioness growled horribly and struck. The Babangos, terrified, turned their eyes in the direction of the sounds; and then the lion charged straight for them, his thunderous roar shaking the ground. The savages turned and fled, leaving their two victims and the witch-doctor in the path of the carnivore.

It all happened so quickly that the lion was above Mullargan before he could gain his feet. For a moment the great beast stood glaring down at the prostrate man, who lay paralyzed with fright, staring back into those terrifying eyes. He smelled the fetid breath and saw the yellow fangs and the drooling jowls, and he saw something else—something that filled him with wonder and amazement—as Tarzan launched himself from the tree full upon the back of the great cat.

Mullargan leaped to his feet then and backed away, but was held by fascinated horror as he waited for the lion to kill the man. Marks scrambled up and tried to climb the tree, clawing at the great bole in a frenzy of terror. The lioness had dragged the woman from the stream and was carrying her off into the forest, her agonized screams rising above all other sounds.

Mullargan wished to run away, but he could not. He stood fixed to the ground, watching the incredible. Tarzan's legs were locked around the small of the lion's body, his steel-thewed arms encircling the black-maned neck. The lion reared upon his hind feet, striking futilely at the man-thing upon his back; and mingled with his roaring and his growling were the growls of the man. It was the latter which froze Mullargan's blood.

He saw the lion throw himself to the ground and roll over upon the man in a frantic effort to dislodge him, but when he came to his feet again the man was still there. One-punch Mullargan had witnessed many a battle that had brought howls of approval for the strength or courage of the contestants, but never had he seen such strength and courage as were being displayed by this almost naked man in hand-to-hand battle with a lion.

The endurance of a lion is in no measure proportional to its strength, and presently the great cat commenced to tire. For a moment it stood squarely upon all four feet, panting; and in that first moment of opportunity Tarzan released his hold with one hand and drew his hunting-knife from its scabbard. At the movement, the lion wheeled and sought to seize his antagonist. The knife flashed in the firelight and the long blade sank deep behind the tawny shoulder. Voicing a hideous roar, the beast reared and leaped; and again the blade was driven home. In a paroxysm of pain and rage, the great cat leaped high into the air. Again the blade was buried in its side. Three times the point had reached the lion's heart; and at last it rolled over on its side, quivered convulsively and lay still.

Tarzan sprang erect and placed a foot upon the carcass of his kill, and raising his face to the heavens voiced the hideous victory cry of the bull ape. Marks' knees gave beneath him, and he sat down suddenly. Mullargan felt the hairs on his scalp rise. The Babangos, who had run into the forest to escape the lion, kept on running to escape the nameless horror of the weird cry.

"Come!" commanded Tarzan; and led the two men toward the plain—away from captivity and death and the cannibal Babangos.

Next day, Marks and Mullargan were in camp with Melton. Tarzan and the Waziri were preparing to leave in pursuit of the Babangos, to punish them and drive them from the country.

Before the ape-man left, he confronted the two Americans.

"Get out of Africa," he commanded, "and never come back."

"Never's too damn' soon for me," said Mullargan.

"Listen, Mister," said Marks "I'll guarantee you one hundred G. if you'll come back to Noo York an' fight for me."

Tarzan turned and walked away, joining the Waziri, who were already on the march. Nkima sat upon his shoulder and called the tarmangani vile names.

Marks spread his hands, palms up. "Can you beat it, kid?" he demanded. "He turns down one hundred G. cold! But it's a good thing for you he did—he'd have taken that champeenship away from you in one round."

"Who?" demanded One-punch Mullargan. "Dat bum?"