Chapter 34 - The Adventures of a Lost Family in the Wilderness by Mayne Reid

A Grand Bee-Hunt

“Next day we had a warm, sunshiny day—just such an one as would bring the bees out. After breakfast we all set forth for the openings, in high spirits at the prospect of the sport we should have. Harry was more eager than any of us. He had heard a good deal about bee-hunters; and was very desirous of knowing how they pursued their craft. He could easily understand that, when a bee-tree was once found, it could be cut down with an axe and split open, and the honey taken from it. All this would be very easily done. But how were bee-trees found? That was the puzzle; for, as I have before observed, these trees do not differ in appearance from others around them; and the hole by which the bees enter is usually so high up, that one cannot see these little insects from the ground. One might tell it to be a bee’s nest, if his attention were called to it; for the bark around the entrance, like that of the squirrel’s, is always discoloured, in consequence of the bees alighting upon it with their moist feet. But then one may travel a long while through the woods before chancing to notice this. Bee-trees are sometimes found by accident; but the regular bee-hunter does not depend upon this, else his calling would be a very uncertain one. There is no accident in the way he goes to work. He seeks for the nest, and is almost sure to find it—provided the ground be open enough to enable him to execute his manoeuvres. I may here remark that, wherever bees take up their abode, there is generally open tracts in their neighbourhood, or else flower-bearing trees—since in very thick woods under the deep dark shadow of the foliage, flowers are more rare, and consequently the food of the bees more difficult to be obtained. These creatures love the bright glades and sunny openings, often met with in the prairie-forests of the wild West.

“Well, as I have said, we were all eager to witness how our bee-hunter, Cudjo, would set about finding the bee-tree—for up to this time he had kept the secret to himself, to the great tantalisation of Harry, whose impatience had now reached its maximum of endurance. The implements which Cudjo had brought along with him—or as he called them, the ‘fixins’—were exceedingly simple in their character. They consisted of a drinking-glass—fortunately we had one that had travelled safely in our great mess-chest—a cup-full of maple molasses, and a few tufts of white wool taken from the skin of a rabbit. ‘How was he going to use these things?’ thought Harry, and so did we all—for none of us knew anything of the process, and Cudjo seemed determined to keep quiet about his plans, until he should give us a practical illustration of them.

“At length we arrived at the glades, and entered one of the largest of them, where we halted. Pompo was taken from the cart, and picketed upon the grass; and we all followed Cudjo—observing every movement that he made. Harry’s eyes were on him like a lynx, for he feared lest Cudjo might go through some part of the operation without his seeing or understanding it. He watched him, therefore, as closely as if Cudjo had been a conjuror, and was about to perform some trick. The latter said nothing, but went silently to work—evidently not a little proud of his peculiar knowledge, and the interest which he was exciting by it.

“There was a dead log near one edge of the opening. To this the bee-hunter proceeded; and, drawing out his knife, scraped off a small portion of the rough bark—so as to render the surface smooth and even. Only a few square inches of the log were thus polished and levelled. That would be enough for his purpose. Upon the spot thus prepared, he poured out a quantity of the molasses—a small quantity, forming a little circle about the size of a penny piece. He next took the glass, and wiped it with the skirt of his coat until it was as clear as a diamond. He then proceeded among the flowers in search of a bee.

“One was soon discovered nestling upon the blossom of a helianthus. Cudjo approached it stealthily, and with an adroit movement inverted the glass upon it, so as to inclose both bee and flower; at the same instant one of his hands—upon which was a strong buckskin glove—was slipped under the mouth of the glass, to prevent the bee from getting out; and, nipping the flower stalk between his fingers, he bore off both the bee and the blossom.

“On arriving at the log, the flower was taken out of the glass by a dexterous movement, and thrown away. The bee still remained, buzzing up against the bottom of the glass—which, of course, was now the top, for Cudjo had held it all the while inverted on his palm. The glass was then set upon the log, mouth downwards, so as to cover the little spot of molasses; and it was thus left, while we all stood around to watch it.

“The bee, still frightened by his captivity, for some time kept circling around the upper part of the glass—seeking, very naturally, for an egress in that direction. His whirring wings, however, soon came in contact with the top of the vessel; and he was flung down right into the molasses. There was not enough of the ‘treacle’ to hold him fast; but having once tasted of its sweets, he showed no disposition to leave it. On the contrary, he seemed to forget all at once that he was a captive; and thrusting his proboscis into the honeyed liquid, he set about drinking it like a good fellow.

“Cudjo did not molest him until he had fairly gorged himself; then, drawing him gently aside with the rim of the glass, he separated him from his banquet. He had removed his gloves, and cautiously inserting his naked hand he caught the bee—which was now somewhat heavy and stupid—between his thumb and forefinger. He then raised it from the log; and turning it breast upward, with his other hand he attached a small tuft of the rabbit wool to the legs of the insect. The glutinous paste with which its thighs were loaded enabled him to effect this the more easily. The wool, which was exceedingly light, was now ‘flaxed out,’ in order to make it show as much as possible, while, at the same time, it was so arranged as not to come in contact with the wings of the bee and hinder its flight. All this did Cudjo with an expertness which surprised us, and would have surprised any one who was a stranger to the craft of the bee-hunter. He performed every operation with great nicety, taking care not to cripple the insect; and, indeed, we did not injure it in the least—for Cudjo’s fingers, although none of the smallest, were as delicate in the touch as those of a fine lady.

“When everything was arranged, he placed the bee upon the log again, laying it down very gently.

“The little creature seemed quite astounded at the odd treatment which it was receiving; and for a few seconds remained motionless upon the log; but a warm sunbeam glancing down upon it soon restored it to its senses; and perceiving that it was once more free, it stretched its translucent wings and rose suddenly into the air. It mounted straight upward, to a height of thirty or forty feet; and then commenced circling around, as we could see by the white wool that streamed after it.

“It was now that Cudjo’s eyes rolled in good earnest. The pupils seemed to be dilated to twice their usual size, and the great balls appeared to tumble about in their sockets, as if there was nothing to hold them. His head, too, seemed to revolve, as if his short thick neck had been suddenly converted into a well-greased pivot, and endowed with rotatory motion!

“After making several circles through the air, the insect darted off for the woods. We followed it with our eyes as long as we could; but the white tuft was soon lost in the distance, and we saw no more of it. We noticed that it had gone in a straight line, which the bee always follows when returning loaded to his hive—hence an expression often heard in western America, the ‘bee-line,’ and which has its synonym in England in the phrase, ‘as the crow flies.’ Cudjo knew it would keep on in this line, until it had reached the tree where its nest was; consequently, he was now in possession of one link in the chain of his discovery—the direction of the bee-tree from the point where we stood.

“But would this be enough to enable him to find it? Evidently not. The bee might stop on the very edge of the woods, or it might go twenty yards beyond, or fifty, or perhaps a quarter of a mile, without coming to its tree. It was plain, then, to all of us, that the line in which the tree lay was not enough, as without some other guide one might have searched along this line for a week without finding the nest.

“All this knew Cudjo before; and, of course, he did not stop a moment to reflect upon it then. He had carefully noted the direction taken by the insect, which he had as carefully ‘marked’ by the trunk of a tree which grew on the edge of the glade, and in the line of the bee’s flight. Another ‘mark’ was still necessary to record the latter, and make things sure. To do this, Cudjo stooped down, and with his knife cut an oblong notch upon the bark of the log, which pointed lengthwise in the direction the bee had taken. This he executed with great precision. He next proceeded to the tree which he had used as a marker, and ‘blazed’ it with his axe.

“‘What next?’ thought we. Cudjo was not long in showing us what was to be next. Another log was selected, at a point, at least two hundred yards distant from the former one. A portion of this was scraped in a similar manner, and molasses poured upon the clear spot as before. Another bee was caught, imprisoned under the glass, fed, hoppled with wool, and then let go again. To our astonishment, this one flew off in a direction nearly opposite to that taken by the former.

“‘Neber mind,’ said Cudjo, ‘so much de better—two bee-tree better than one.’

“Cudjo marked the direction which the latter had taken, precisely as he had done with the other.

“Without changing the log a third bee was caught and ‘put through.’ This one took a new route, different from either of his predecessors.

“‘Gollies! Massa!’ cried Cudjo, ‘dis valley am full ob honey. Three bee-trees at one stand!’ and he again made his record upon the log.

“A fourth bee was caught, and, after undergoing the ceremony, let go again. This one evidently belonged to the same hive as the first, for we saw that it flew toward the same point in the woods. The direction was carefully noted, as before. A clue was now found to the whereabouts of one hive—that of the first and fourth bees. That was enough for the present. As to the second and third, the records which Cudjo had marked against them would stand good for the morrow or any other day; and he proceeded to complete the ‘hunt’ after the nest of Numbers 1 and 4.

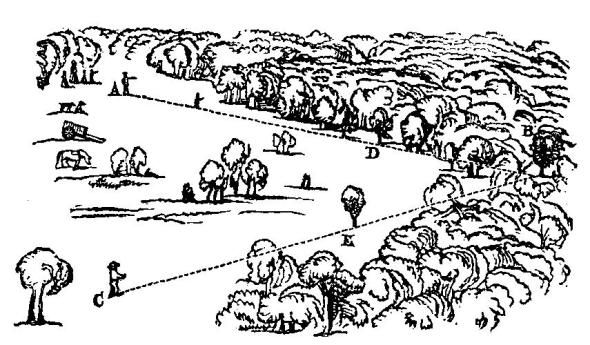

“We had all by this time acquired an insight into the meaning of Cudjo’s manoeuvres, and we were able to assist him. The exact point where the bee-tree grew was now determined. It stood at the point where the two lines made by bees, Numbers 1 and 4, met each other. It would be found at the very apex of this angle—wherever it was. But that was the next difficulty—to get at this point. There would have been no difficulty about it, had the ground been open, or so that we could have seen to a sufficient distance through the woods. This could have been easily accomplished by two of us stationing ourselves—one at each of the two logs—while a third individual moved along either of the lines. The moment this third person should appear on both lines at once, he would of course be at the point of intersection; and at this point the bee-tree would be found. I shall explain this by a diagram.

“Suppose that A and C were the two logs, from which the bees, Numbers 1 and 4, had respectively taken their flight; and suppose A B and C B to be the directions in which they had gone. If they went directly home—which it was to be presumed they both did—they would meet at their nest at some point B. This point could not be discovered by seeing the bees meeting at it, for they were already lost sight of at short distances from A and C. But without this, had the ground been clear of timber, we could easily have found it in the following manner:—I should have placed myself at log A, while Cudjo stationed himself at C. We should then have sent one of the boys—say Harry—along the line A D. This, you must observe, is a fixed line, for D was already a marked point. After reaching D, Harry should continue on, keeping in the same line. The moment, therefore, that he came under the eye of Cudjo—who would be all this while glancing along C E, also a fixed line—he would then be on both lines at once, and consequently at their point of intersection. This, by all the laws of bee-hunting, would be the place to find the nest; and, as I have said, we could easily have found it thus, had it not been for the trees. But these intercepted our view, and therein lay the difficulty; for the moment Harry should have passed the point D, where the underwood began, he would have been lost to our sight, and, of course, of no farther use in establishing the point B.

“For myself, I could not see clearly how this difficulty was to be got over—as the woods beyond D and E were thick and tangled. The thing was no puzzle to Cudjo, however. He knew a way of finding B, and the bee-tree as well, and he went about it at once.

“Placing one of the boys at the station A, so that he could see him over the grass, he shouldered his axe, and moved off along the line A D. He entered the woods at D, and kept on until he had found a tree from which both A and D were visible, and which lay exactly in the same line. This tree he ‘blazed.’ He then moved a little farther, and blazed another, and another—all on the continuation of the line A D—until we could hear him chopping away at a good distance in the woods. Presently he returned to the point E; and, calling to one of us to stand for a moment at C, he commenced ‘blazing’ backwards, on the continuation of C E. We now joined him—as our presence at the logs was no longer necessary to his operations.

“At a distance of about two hundred yards from the edge of the glade, the blazed lines were seen to approach each other. There were several very large trees at this point. Cudjo’s ‘instinct’ told him, that in one of these the bees had their nest. He flung down his axe at length, and rolled his eyes upwards. We all took part in the search, and gazed up, trying to discover the little insects that, no doubt, were winging their way among the high branches.

“In a few moments, however, a loud and joyful exclamation from Cudjo proclaimed that the hunt was over—the bee-tree was found!

“True enough, there was the nest, or the entrance that led to it, away high up on a giant sycamore. We could see the discoloration on the bark caused by the feet of the bees, and even the little creatures themselves crowding out and in. It was a large tree, with a cavity at the bottom big enough to have admitted a full-sized man, and, no doubt, hollow up to the place where the bees had constructed their nest.

“As we had spent many hours in finding it, and the day was now well advanced, we concluded to leave farther operations for the morrow, when we should fell it, and procure the delicious honey. With this determination, and well satisfied with our day’s amusement, we returned to our house.”