The Fairies Of Pesth [1] by Eugene Field

An old poet walked alone in a quiet valley. His heart was heavy, and the voices of Nature consoled him. His life had been a lonely and sad one. Many years ago a great grief fell upon him, and it took away all his joy and all his ambition. It was because he brooded over his sorrow, and because he was always faithful to a memory, that the townspeople deemed him a strange old poet; but they loved him and they loved his songs,—in his life and in his songs there was a gentleness, a sweetness, a pathos that touched every heart. "The strange, the dear old poet," they called him.

Evening was coming on. The birds made no noise; only the whip-poor-will repeated over and over again its melancholy refrain in the marsh beyond the meadow. The brook ran slowly, and its voice was so hushed and tiny that you might have thought that it was saying its prayers before going to bed.

The old poet came to the three lindens. This was a spot he loved, it was so far from the noise of the town. The grass under the lindens was fresh and velvety. The air was full of fragrance, for here amid the grass grew violets and daisies and buttercups and other modest wild-flowers. Under the lindens stood old Leeza, the witchwife.

"Take this," said the poet to old Leeza, the witchwife; and he gave her a silver piece.

"You are good to me, master poet," said the witchwife. "You have always been good to me. I do not forget, master poet, I do not forget."

"Why do you speak so strangely?" asked the old poet. "You mean more than you say. Do not jest with me; my heart is heavy with sorrow."

"I do not jest," answered the witchwife. "I will show you a strange thing. Do as I bid you; tarry here under the lindens, and when the moon rises, the Seven Crickets will chirp thrice; then the Raven will fly into the west, and you will see wonderful things, and beautiful things you will hear."

Saying this much, old Leeza, the witch-wife, stole away, and the poet marvelled at her words. He had heard the townspeople say that old Leeza was full of dark thoughts and of evil deeds, but he did not heed these stories.

"They say the same of me, perhaps," he thought. "I will tarry here beneath the three lindens and see what may come of this whereof the witch wife spake."

The old poet sat amid the grass at the foot of the three lindens, and darkness fell around him. He could see the lights in the town away off; they twinkled like the stars that studded the sky. The whip-poor-will told his story over and over again in the marsh beyond the meadow, and the brook tossed and talked in its sleep, for it had played too hard that day.

"The moon is rising," said the old poet. "Now we shall see."

The moon peeped over the tops of the far-off hills. She wondered whether the world was fast asleep. She peeped again. There could be no doubt; the world was fast asleep,—at least so thought the dear old moon. So she stepped boldly up from behind the distant hills. The stars were glad that she came, for she was indeed a merry old moon.

The Seven Crickets lived in the hedge. They were brothers, and they made famous music. When they saw the moon in the sky they sang "chirp-chirp, chirp-chirp, chirp-chirp," three times, just as old Leeza, the witchwife, said they would.

"Whir-r-r!" It was the Raven flying out of the oak-tree into the west. This, too, was what the old witchwife had foretold. "Whir-r-r" went the two black wings, and then it seemed as if the Raven melted into the night. Now, this was strange enough, but what followed was stranger still.

Hardly had the Raven flown away, when out from their habitations in the moss, the flowers, and the grass trooped a legion of fairies,—yes, right there before the old poet's eyes appeared, as if by magic, a mighty troop of the dearest little fays in all the world.

Each of these fairies was about the height of a cambric needle. The lady fairies were, of course, not so tall as the gentleman fairies, but all were of quite as comely figure as you could expect to find even among real folk. They were quaintly dressed; the ladies wearing quilted silk gowns and broadbrim hats with tiny feathers in them, and the gentlemen wearing curious little knickerbockers, with silk coats, white hose, ruffled shirts, and dainty cocked hats.

"If the witchwife had not foretold it I should say that I dreamed," thought the old poet. But he was not frightened. He had never harmed the fairies, therefore he feared no evil from them.

One of the fairies was taller than the rest, and she was much more richly attired. It was not her crown alone that showed her to be the queen. The others made obeisance to her as she passed through the midst of them from her home in the bunch of red clover. Four dainty pages preceded her, carrying a silver web which had been spun by a black-and-yellow garden spider of great renown. This silver web the four pages spread carefully over a violet leaf, and thereupon the queen sat down. And when she was seated the queen sang this little song:

"From the land of murk and mist

Fairy folk are coming

To the mead the dew has kissed,

And they dance where'er they list

To the cricket's thrumming.

"Circling here and circling there,

Light as thought and free as air,

Hear them cry, 'Oho, oho,'

As they round the rosey go.

"Appleblossom, Summerdew,

Thistleblow, and Ganderfeather!

Join the airy fairy crew

Dancing on the swaid together!

Till the cock on yonder steeple

Gives all faery lusty warning,

Sing and dance, my little people,—

Dance and sing 'Oho' till morning!"

The four little fairies the queen called to must have been loitering. But now they came scampering up,—Ganderfeather behind the others, for he was a very fat and presumably a very lazy little fairy.

"The elves will be here presently," said the queen, "and then, little folk, you shall dance to your heart's content. Dance your prettiest to-night, for the good old poet is watching you."

"Ah, little queen," cried the old poet, "you see me, then? I thought to watch your revels unbeknown to you. But I meant you no disrespect,—indeed, I meant you none, for surely no one ever loved the little folk more than I."

"We know you love us, good old poet," said the little fairy queen, "and this night shall give you great joy and bring you into wondrous fame."

These were words of which the old poet knew not the meaning; but we, who live these many years after he has fallen asleep,—we know the meaning of them.

Then, surely enough, the elves came trooping along. They lived in the further meadow, else they had come sooner. They were somewhat larger than the fairies, yet they were very tiny and very delicate creatures. The elf prince had long flaxen curls, and he was arrayed in a wonderful suit of damask web, at the manufacture of which seventy-seven silkworms had labored for seventy-seven days, receiving in payment therefor as many mulberry leaves as seven blue beetles could carry and stow in seven times seven sunny days. At his side the elf prince wore a sword made of the sting of a yellow-jacket, and the hilt of this sword was studded with the eyes of unhatched dragon-flies, these brighter and more precious than the most costly diamonds.

The elf prince sat beside the fairy queen. The other elves capered around among the fairies. The dancing sward was very light, for a thousand and ten glowworms came from the marsh and hung their beautiful lamps over the spot where the little folk were assembled. If the moon and the stars were jealous of that soft, mellow light, they had good reason to be.

The fairies and elves circled around in lively fashion. Their favorite dance was the ring-round-a-rosey which many children nowadays dance. But they had other measures, too, and they danced them very prettily.

"I wish," said the old poet, "I wish that I had my violin here, for then I would make merry music for you."

The fairy queen laughed. "We have music of our own," she said, "and it is much more beautiful than even you, dear old poet, could make."

Then, at the queen's command, each gentleman elf offered his arm to a lady fairy, and each gentleman fairy offered his arm to a lady elf, and so, all being provided with partners, these little people took their places for a waltz. The fairy queen and the elf prince were the only ones that did not dance; they sat side by side on the violet leaf and watched the others. The hoptoad was floor manager; the green burdock badge on his breast showed that.

"Mind where you go—don't jostle each other," cried the hoptoad, for he was an exceedingly methodical fellow, despite his habit of jumping at conclusions.

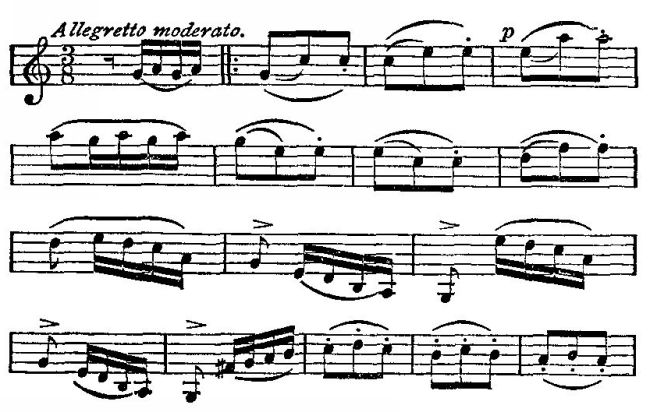

Then, when all was ready, the Seven Crickets went "chirp-chirp, chirp-chirp, chirp-chirp," three times, and away flew that host of little fairies and little elves in the daintiest waltz imaginable:—

The old poet was delighted. Never before had he seen such a sight; never before had he heard so sweet music. Round and round whirled the sprite dancers; the thousand and ten glowworms caught the rhythm of the music that floated up to them, and they swung their lamps to and fro in time with the fairy waltz. The plumes in the hats of the cunning little ladies nodded hither and thither, and the tiny swords of the cunning little gentlemen bobbed this way and that as the throng of dancers swept now here, now there. With one tiny foot, upon which she wore a lovely shoe made of a tanned flea's hide, the fairy queen beat time, yet she heard every word which the gallant elf prince said. So, with the fairy queen blushing, the mellow lamps swaying, the elf prince wooing, and the throng of little folk dancing hither and thither, the fairy music went on and on:—

"Tell me, my fairy queen," cried the old poet, "whence comes this fairy music which I hear? The Seven Crickets in the hedge are still, the birds sleep in their nests, the brook dreams of the mountain home it stole away from yester morning. Tell me, therefore, whence comes this wondrous fairy music, and show me the strange musicians that make it."

"Look to the grass and the flowers," said the fairy queen. "In every blade and in every bud lie hidden notes of fairy music. Each violet and daisy and buttercup,—every modest wild-flower (no matter how hidden) gives glad response to the tinkle of fairy feet. Dancing daintily over this quiet sward where flowers dot the green, my little people strike here and there and everywhere the keys which give forth the harmonies you hear."

Long marvelled the old poet. He forgot his sorrow, for the fairy music stole into his heart and soothed the wound there. The fairy host swept round and round, and the fairy music went on and on.

"Why may I not dance?" asked a piping voice. "Please, dear queen, may I not dance, too?"

It was the little hunchback that spake,—the little hunchback fairy who, with wistful eyes, had been watching the merry throng whirl round and round.

"Dear child, thou canst not dance," said the fairy queen, tenderly; "thy little limbs are weak. Come, sit thou at my feet, and let me smooth thy fair curls and stroke thy pale cheeks."

"Believe me, dear queen," persisted the little hunchback, "I can dance, and quite prettily, too. Many a time while the others made merry here I have stolen away by myself to the brookside and danced alone in the moonlight,—alone with my shadow. The violets are thickest there. 'Let thy halting feet fall upon us, Little Sorrowful,' they whispered, 'and we shall make music for thee.' So there I danced, and the violets sang their songs for me. I could hear the others making merry far away, but I was merry, too; for I, too, danced, and there was none to laugh."

"If you would like it, Little Sorrowful," said the elf prince, "I will dance with you."

"No, brave prince," answered the little hunchback, "for that would weary you. My crutch is stout, and it has danced with me before. You will say that we dance very prettily,—my crutch and I,—and you will not laugh, I know."

Then the queen smiled sadly; she loved the little hunchback and she pitied her.

"It shall be as you wish," said the queen. The little hunchback was overjoyed.

"I have to catch the time, you see," said she, and she tapped her crutch and swung one little shrunken foot till her body fell into the rhythm of the waltz.

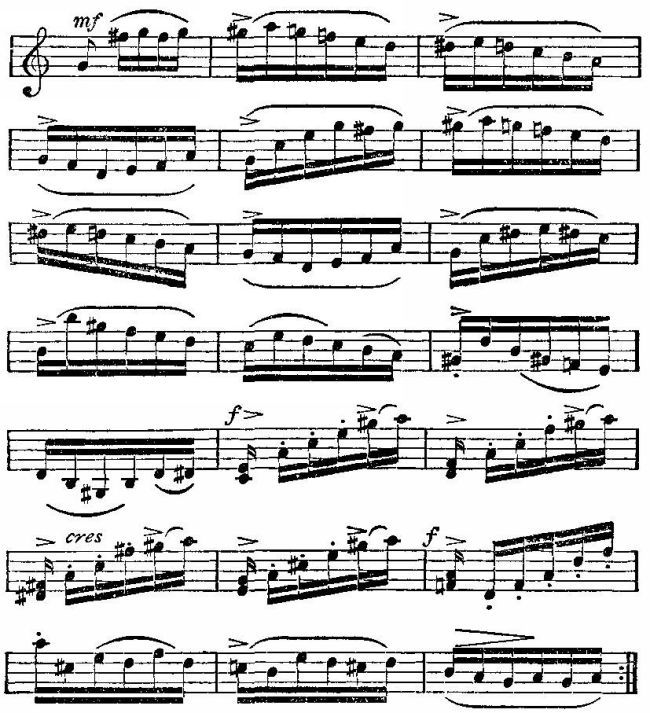

Far daintier than the others did the little hunchback dance; now one tiny foot and now the other tinkled on the flowers, and the point of the little crutch fell here and there like a tear. And as she danced, there crept into the fairy music a tenderer cadence, for (I know not why) the little hunchback danced ever on the violets, and their responses were full of the music of tears. There was a strange pathos in the little creature's grace; she did not weary of the dance: her cheeks flushed, and her eyes grew fuller, and there was a wondrous light in them. And as the little hunchback danced, the others forgot her limp and felt only the heart-cry in the little hunchback's merriment and in the music of the voiceful violets.

Now all this saw the old poet, and all this wondrously beautiful music he heard. And as he heard and saw these things, he thought of the pale face, the weary eyes, and the tired little body that slept forever now. He thought of the voice that had tried to be cheerful for his sake, of the thin, patient little hands that had loved to do his bidding, of the halting little feet that had hastened to his calling.

"Is it thy spirit, O my love?" he wailed, "Is it thy spirit, O dear, dead love?"

A mist came before his eyes, and his heart gave a great cry.

But the fairy dance went on and on. The others swept to and fro and round and round, but the little hunchback danced always on the violets, and through the other music there could be plainly heard, as it crept in and out, the mournful cadence of those tenderer flowers.

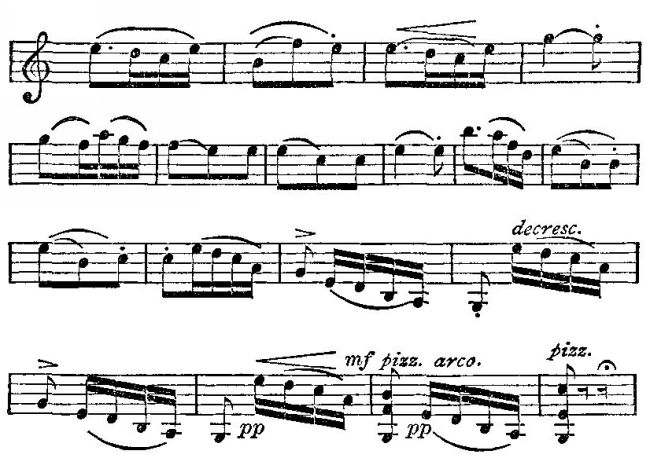

And, with the music and the dancing, the night faded into morning. And all at once the music ceased and the little folk could be seen no more. The birds came from their nests, the brook began to bestir himself, and the breath of the new-born day called upon all in that quiet valley to awaken.

So many years have passed since the old poet, sitting under the three lindens half a league the other side of Pesth, saw the fairies dance and heard the fairy music,—so many years have passed since then, that had the old poet not left us an echo of that fairy waltz there would be none now to believe the story I tell.

Who knows but that this very night the elves and the fairies will dance in the quiet valley; that Little Sorrowful will tinkle her maimed feet upon the singing violets, and that the little folk will illustrate in their revels, through which a tone of sadness steals, the comedy and pathos of our lives? Perhaps no one shall see, perhaps no one else ever did see, these fairy people dance their pretty dances; but we who have heard old Robert Volkmann's waltz know full well that he at least saw that strange sight and heard that wondrous music.

And you will know so, too, when you have read this true story and heard old Volkmann's claim to immortality.

1887.

[Footnote 1: The music arranged by Mr. Theodore Thomas.]