The Golden Cockerel Pushkin's poems for children

In country far, and days long gone,

There lived a famous Tsar — Dadon.

When young, his strength was held in awe

By all his neighbours: he made war

Whenever he declared it right.

With age, he grew less keen to fight,

Desiring his deserved peace: Struggle should stop; war’s clamour cease.

His down-trod neighbours saw their chance,

And armed with dagger, sword and lance,

Attacked his frontiers at will,

Making the old Tsar maintain still

An army of twelve thousand men,

With horses, weaponry, and then

Appoint highly-paid generals

To guard the kingdom’s threatened walls.

But, when they watched the west, ’twas sure

The eastern border, less secure

Would be where hostile troops appeared,

The danger greatest where least feared.

Eastward the generals sally forth,

Only to find that now the north

Border is where the danger lies.

Tormented thus, Tsar Dadon cries

Hot tears of rage. He cannot sleep.

O’er land foes stream; then from the deep.

What is life worth, when so assailed?

So, desperate, Dadon availed

Himself of magic, turning to

A sorcerer (and eunuch, too),

Interpreter of omens, stars,

Bird-flights, and such particulars.

The courtier, sent to call the sage,

Implied there’d be a handsome wage.

Arrived at court, the wise old man

Disclosed with confidence his plan:

The golden cockerel he drew

Out from his bag by magic knew

Who would attack, and when, and where,

Enabling generals to prepare.

“Just watch and listen,” said the sage.

Dadon responded: “I engage,

If this be so, to grant as fee

Whatever you request of me.

So, set the cock, as weather-vane

Upon the highest spire. Remain

Watchful, attentive; he will show

You when to arm, and where to go.

Superior intelligence

Will always be the best defense.”

And so it proves: whenever threats

Appear, the faithful sentry sets

His crimson crest in that direction

Whence comes th’incipient insurrection.

“Kiri-ku-ku,” he cries, “Hear me,

And rule long years, from worry free.”

Discovered once, and caused to flee,

Then thrice more routed, th’enemy

Lose heart, respect again the will

Of Tsar Dadon, their master still.

A year so passes, then one more.

Dadon expects another score.

One dawn however, courtiers wake

The Tsar, pale-faced, with hearts a-quake:

“The cockerel, Lord, calls you to arms.

Protect us, holy Tsar, from harms.”

Dadon, half-sleeping, asks: “What? What?

Have you your manners quite forgot?”

“Forgive us, but the cock,” they say,

Is adamant, brooks no delay.”

The people panic. Only you

Can their else-mut’nous fears subdue.

Rousing himself, old Tsar Dadon

Declares he’ll send his elder son

Southward, whose army shall repel

The foe which that true cockerel

Has there disclosed. “Now back to bed

“The enemy’s as good as dead.”

The Tsar proclaims, “I too retire.

Fear not. My spy’s still on his spire.”

Wars oft entail a news black-out:

Was there a victory? Or rout?

Who has prevailed? How stands the score

Of dead? And were ours less or more

Than theirs? No word for seven days

The Court’s disquietude allays.

Then, on the eighth, the cockerel’s

Loud cry the peace again dispels.

This time his crimson comb points north.

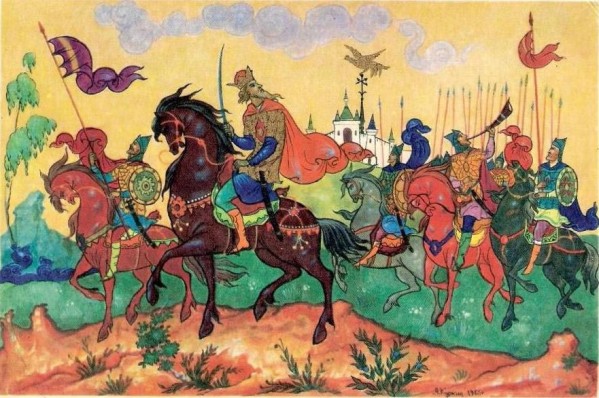

Dadon ordains to sally forth

His younger son, leading a force,

So rich in armour, men and horse,

That no known foe could fail to yield,

Such weapons Dadon’s troops now wield.

They march; are gone. Silence profound

Envelops them, as though the ground

Had opened, as it did in truth,

To swallow up all Hamlin’s youth

When its authorities displayed

Indiff’rence to a promise made.

Ill omen! For another week

The golden cock’s sharp close-clamped beak

Swings slowly round, clock-wise; and then

Swings just as slowly back again.

But, when the eighth day dawns, the bird

Crows the alarm. Grim-faced, a third

Army the Tsar himself leads out.

Ahead, a solitary scout,

Follows the blood-red setting sun.

Dadon’s last campaign has begun.

Long nights and days the soldiers march:

Frost cramps their feet; then hot winds parch

Their throats. They seek, but find no trace

Of battles, of the bloody chase

Of fugitives, of funeral mounds.

No rallying cries, no trumpet’s sounds

Waft to the ears of Tsar Dadon,

As puzzled, tired, he trudges on.

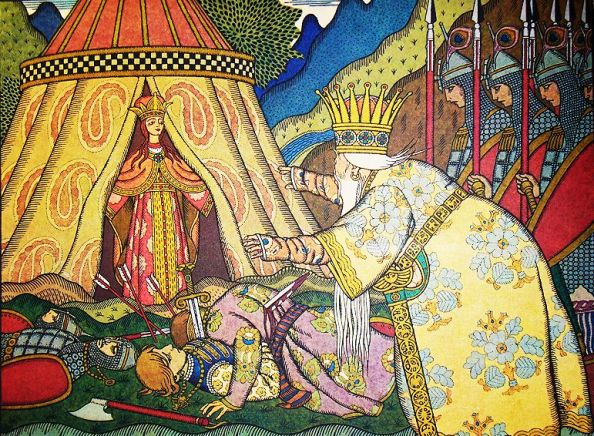

Just when he’s topped a mountain pass,

Descending valley-ward,… alas!

What frightful vision lies before

Him: scattered round a silken tent

Lie those two armies Dadon sent

In his defence. Now all are dead;

And his two sons, unhelmeted,

Hold swords plunged in each other’s breast,

Hatred in four glazed eyes expressed.

Oh, my dear children! Who has snared

My falcons? What magician dared

Villainy in their hearts to stir,

To make of each a murderer?

His soldiers raise such grievous groan

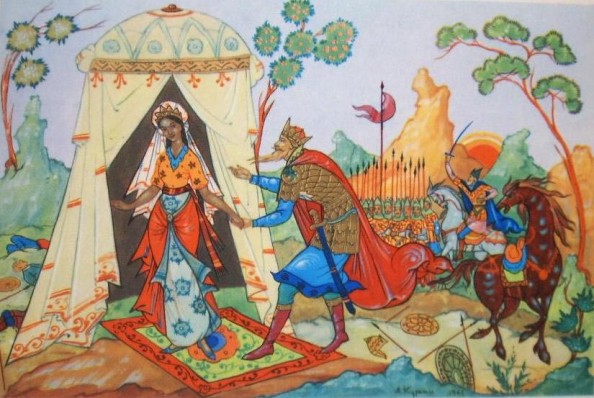

It seems the very mountains moan. But then the curtains of the tent

Are flung aside. The hands that rent

Them, diamond-ringed and braceleted,

The stately figure, noble head,

Royalty’s redolence express..

A Shamakhanskaya Princess

She is, who sees Dadon, and smiles.

Her beck’ning finger so beguiles

Him that, bewitched, his sons forgot

The Tsar accepts his destined lot:

Her rule, indeed her domination.

He walks, surrendering his nation,

Into the silken-wall’ed tent,

Wherein his next eight nights are spent

In (who can doubt?) those rites of passion

To detail which is out of fashion,

Feasting ‘tween-times on everything

Our chefs declare «fit for a king».

At last begins the homeward course.

The maiden, mounted on his horse,

Caresses the still-love-sick Tsar.

The soldiers grumble; yet they are

Eager to tell their waiting friends

(With what imagination lends

Their memories) fantastic stuff

And nonsense. Sure, they’ve seen enough!

Rumours have reached the capital

Before them. At its drawbridge, all

The people wait in trepidation

To see the ruler of the nation

Approaching with his new consort,

Of whom men variously report

She is a witch, a whore, a queen.

Never before have such things been.

They greet their Tsar. His grave salute

Befits his rank; but his acute

Eye has detected in the crowd

That eunuch-sage whose cockerel’s loud

Uproar had saved the threatened state.

“Approach, old man,” Dadon invites,

“I grant whatever gift requites

You for your golden cockerel

Whose sentry-duty served so well.”

“I just desire,” the wizard says,

The Shamakhanskaya Princess.

Come now, my lady, we must leave.”

Th’astonished Tsar cannot believe

His ears. “What? what? Take my princess?

And you a eunuch! I confess

I never heard a better joke.

But seriously, when I spoke

Of paying you right handsomely

I also meant in reason. See,

I’ll give you half my treasury;

A lordship; and, if lechery

Indeed attracts you, all the whores

Whom you can satisfy.”

With force

The wizard answers: “Satisfied

I’ll be only with her as bride.

Give me the Shamakhan Princess.

I’ll be content with nothing less.”

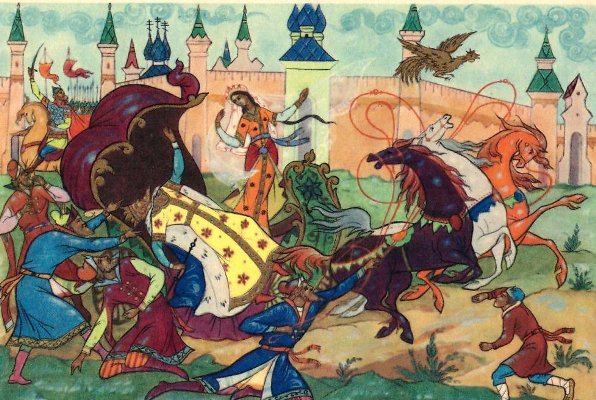

“Take nothing then,”Tsar Dadon said.

His sword-swipe smote the old man dead.

The crowd was dumbstruck; but the maid,

By this aggression undismayed,

Burst out in laughter, peal on peal,

As though by laughing to reveal

Her full involvement in the plan

To trick and then destroy a man.

The Tsar, though startled, deigns to smile.

Then on, along the Royal Mile.

The crowd begins a careful cheer,

Until a whir of wings they hear

And see a bird with lance-like beak,

A golden bird, with feathers sleek,

Dive at the Tsar, piercing his head.

Dadon groans once, falls, and is dead.

Where’s she who was to be his queen?

Vanished, as though she’d never been.

The story’s false; but in it lies

Some truth, seen but by inward eyes.

Illustrations by Kurkin